|

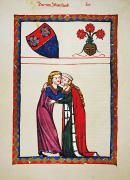

| A Medieval Depiction of the Marriage of Princess Isabella - the Core of the Controvery |

In November 1190, Princess Isabella of Jerusalem, then 18 years old, was forcibly removed from the tent she was sharing with her husband Humphrey of Toron in the Christian camp besieging the city of Acre. Just days earlier, her elder sister, Queen Sibylla, had died, making Isabella the hereditary queen of the all-but-non-existent -- yet symbolically important-- Kingdom of Jerusalem. A short time after her abduction, she married Conrad Marquis de Montferrat, making him, through her, the de facto King of Jerusalem. This high-profile abduction and marriage scandalized the church chroniclers and is often sited to this day as evidence of the perfidy of Conrad de Montferrat and his accomplices. The latter included Isabella’s mother, Maria Comnena, and her step-father, Balian d’Ibelin.

The anonymous author of the Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi (Itinerarium), for example, describes with blistering outrage how Conrad de Montferrat had long schemed to “steal” the throne of Jerusalem, and at last stuck upon the idea of abducting Isabella—a crime he compares to the abduction of Helen of Sparta by Paris of Troy “only worse.” To achieve his plan, the Itinerarium claims, Conrad “surpassed the deceits of Sinon, the eloquence of Ulysses and the forked tongue of Mithridates.” Conrad, according to this English cleric writing after the fact, set about bribing, flattering and corrupting bishops and barons alike as never before in recorded history. Throughout, the chronicler says, Conrad was aided and abetted by three barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (Sidon, Haifa and Ibelin) who combined (according to our chronicler) “the treachery of Judas, the cruelty of Nero, and the wickedness of Herod, and everything the present age abhors and ancient times condemned.” Really? The author certainly brings no evidence of a single act of treachery, cruelty, or wickedness — beyond this one allleged abduction, which (as we shall see) was hardly a case of rape as we shall see.

Indeed, this chronicler himself admits that Isabella was not removed from Humphrey’s tent by Conrad himself, nor was she handed over to him. On the contrary she was put into the care of clerical “sequesters,” with a mandate to assure her safety and prevent a further abduction, “while a clerical court debated the case for a divorce.” Furthermore, in the very next paragraph our anonymous slanderer of some of the most courageous and pious lords of Jerusalem, declares that although Isabella at first resisted the idea of divorcing her husband Humphrey, she was soon persuaded to consent to divorce because “a woman’s opinion changes very easily” and “a girl is easily taught to do what is morally wrong.”

While the Itinerarium admits that Isabella’s marriage to Humphrey was reviewed by a church court, it hides this fact under the abuse it heaps upon the clerics involved. Another contemporary chronicle, the Lyon continuation of William of Tyre, explains in far more neutral and objective language that that the case hinged on the important principle of consent. By the 12th century, marriage could only be valid in canonical law if both parties (i.e. including Isabella) consented. The issue at hand was whether Isabella had consented to her marriage to Humphrey at the time it was contracted.

The Lyon Continuation further notes that Isabella and Humphrey testified before the church tribunal separately. In her testimony, Isabella asserted she had not consented to her marriage to Humphrey, while Humphrey claimed she had. The Lyon Continuation also provides the colorful detail that another witness, who had been present at Isabella and Humphrey's wedding, at once called Humphrey a liar, and challenged him to prove he spoke the truth in combat. Humphrey, the chronicler says, refused to “take up the gage.” At this point the chronicler states that Humphrey was “cowardly and effeminate.”

|

| In the 12th Century judicial combat was still recognized as a legal means of settling disputes. |

Both accounts (the Itinerarium and the Lyon Continuation) agree that following the testimony and deliberations the Church council ruled that Isabella’s marriage to Humphrey was invalid. There was only one dissenting voice, that of the Archbishop of Canterbury. However, both chroniclers insist that this decision was reached because Conrad corrupted all the other clerics, particularly the Papal legate, the Archbishop of Pisa. The Lyon Continuation claims that the Archbishop of Pisa ruled the marriage invalid and allowed Isabella to marry Conrad only because Conrad promised commercial advantages for Pisa from should he win Isabella and become king. The Itinerarium on the other hand claims Conrad “poured out enormous generosity to corrupt judicial integrity with the enchantment of gold.”

There are a lot of problems with the clerical outrage over Isabella’s “abduction” — not to mention the dismissal of Isabella’s change of heart as the inherent moral frailty of females. There are also problems with the slander heaped on the barons and bishops, who dared to support Conrad de Montferrat's suit for Isabella.

Let’s go back to the basic facts of the case as laid out by the chroniclers themselves but stripped of moral judgements and slander:

- Isabella was removed from Humphrey de Toron’s tent against her will.

- She was not, however, taken by Conrad or raped by him.

- Rather she was turned over to neutral third parties, sequestered and protected by them.

- Meanwhile, a church court was convened to rule on the validity of her marriage to Humphrey.

- The case hinged on the important theological principle of consent. (Note: In the 12th Century, both parties to a marriage had to consent. To consent they had be legally of age. The legal age of consent for girls was 12.)

- Humphrey claimed that Isabella had consented to the marriage, but when challenged by a witness to the wedding he “said nothing” and backed down.

- Isabella, meanwhile, had “changed her mind” and consented to the divorce.

- The court ruled that Isabella's marriage to Humphrey had not been valid.

- On Nov. 25, with either the French Bishop of Beauvais or the Papal Legate himself presiding, Isabella married Conrad. Since a clerical court had just ruled that no marriage was valid without the consent of the bride, we can be confident that she consented to this marriage. In fact, as the Itinerarium so reports (vituperously) reports, “she was not ashamed to say…she went with the Marquis of her own accord.”

To understand what really happened in the siege camp of Acre in November 1190, we need to look beyond what the church chronicles write about the abduction itself.

The story really begins in 1180 when Isabella was just eight years old. Until this time, Isabella had lived in the care and custody of her mother, the Byzantine Princess and Dowager Queen of Jerusalem, Maria Commena. In 1180, King Baldwin IV (Isabella’s half-brother) arranged the betrothal of Isabella to Humphrey de Toron. Having promised this marriage without the consent of Isabella’s mother or step-father, the king ordered the physical removed of Isabella from her mother and step-father’s care and sent her to live with her future husband, his mother and his step-father. The latter was the infamous Reynald de Chatillon, notorious for having seduced the Princess of Antioch, tortured the Archbishop of Antioch, and sacked the Christian island of Cyprus. Isabella was effectively imprisoned in his border fortress at Kerak and his wife, Stephanie de Milly explicitly prohibited Isabella from even visiting her mother for three years.

|

| Kerak in Transjordan, where Isabella was Imprisoned for Three Years |

In November 1183, when Isabella was just eleven years old, Reynald and his wife held a marriage feast to celebrate the wedding of Isabella and Humphrey. They invited all the nobles of the kingdom to witness the feast. Unfortunately, before most of the wedding guests could arrive, Saladin's army surrounded the castle and laid siege to it. The wedding took place, and a few weeks later the army of Jerusalem relieved the castle, chasing Saladin’s forces away.

Note, at the time the wedding took place, Isabella was not only a prisoner of her in-laws, she was only eleven years old. Canonical law in the 12th century, however, established the “age of consent” for girls at 12. Isabella could not legally consent to her wedding, even if she wanted to. The marriage had been planned by the King, however, and carried out by one of the most powerful barons during a crisis. No one seems to have dared challenge it at the time.

At the death of Baldwin V three years later, Isabella’s older sister, Queen Sibylla, was first in line to the throne but found herself opposed by almost the entire High Court of Jerusalem (that constitutionally was required to consent to each new monarch). The opposition sprang not from objections Sibylla herself, but from the fact that the bishops and barons of the kingdom almost unanimously detested her husband, Guy de Lusignan. Although she could not gain the consent of the High Court necessary to make her coronation legal, she managed to convince a minority of the lords secular and ecclesiastical to crown her queen by promising to divorce Guy and choose a new husband. Once anointed, Sibylla promptly betrayed her supporters by declaring that her “new” husband was the same as her old husband: Guy de Lusignan. She then crowned him herself (at least according to some accounts).

|

| The Coronation of Sibylla and Guy as depicted in "The Kingdom of Heaven" |

This struck many people at the time as duplicitous, to say the least, and the majority of the barons and bishops decided that since she had not had their consent in the first place, she and her husband were usurpers. They agreed to crown her younger sister Isabella (now 14 years old) instead. The assumption was that since they commanded far larger numbers of troops than did Sibylla’s supporters (many of whom now felt duped and were dissatisfied anyway, no doubt), they would be able to quickly depose of Sibylla and Guy.

The plan, however, came to nothing because Isabella’s husband, Humphrey de Toron, had no stomach for a civil war (or a crown, it seems), and chose to sneak away in the dark of night to do homage to Sibylla and Guy. The baronial revolt collapsed. Almost everyone eventually did homage to Guy, and he promptly led them all to an avoidable defeat at the Battle of Hattin. With the field army annihilated, the complete occupation of the Kingdom by the forces of Saladin followed – with the important exception of Tyre.

Tyre only avoided the fate of the rest of the kingdom because of the timely arrival of a certain Italian nobleman, Conrad de Montferrat, who rallied the defenders and defied Saladin. Montferrat came from a very good and very well connected family. He was first cousin to both the Holy Roman Emperor and King Louis VII of France. Furthermore, his elder brother had been Sibylla of Jerusalem’s first husband (before Guy), and his younger brother had been married to the daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I. Furthermore, he defended Tyre twice against the vastly superior armies of Saladin, and by holding Tyre he enabled the Christians to retain a bridgehead by which troops, weapons and supplies could be funneled back into the Holy Land for a new crusade to retake Jerusalem. While Conrad was preforming this heroic function, Guy de Lusignan was an (admittedly unwilling) “guest” of Saladin, a prisoner of war following his self-engineered defeat at Hattin.

So at the time of the infamous abduction, Guy was an anointed king, but one who derived his right to the throne from his now deceased wife (Sibylla died in early November 1190, remember), and furthermore a king viewed by most of his subjects as a usurper—even before he’d lost the entire kingdom through his incompetence. It is fair to say that in November 1190 Guy was not popular among the surviving barons and bishops of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and they were eager to see the kingdom pass into the hands of someone they respected and trusted. The death of Sibylla provided the perfect opportunity to crown a new king because with her death the crown legally passed to her sister Isabella, and, according to the Constitution of the Kingdom, the husband of the queen ruled with her as her consort.

The problem faced by the barons and bishops of Jerusalem in 1190, however, was that Isabella was still married to the same man who had betrayed them in 1186: Humphrey de Toron. He was clearly not interested in a crown, and it didn’t help matters that he’d been in a Saracen prison for two years. Perhaps more damning still, he was allegedly “more like a woman than a man: he had a gentle manner and a stammer.”(According to the Itinerarium.)

|

| The Barons of Jerusalem were Still in Force to be Reckoned with in 1190. |

Whatever the reason, we know that the barons and bishops of Jerusalem were not prepared to make the same mistake they had made four years earlier when they had done homage to a man they knew was incompetent (Guy de Lusignan). They absolutely refused to acknowledge Isabella’s right to the throne, unless she had first set aside her unsuitable husband and taken a man acceptable to them. We know this because the Lyon Continuation is based on a lost chronicle written by a certain Ernoul, who as an intimate of the Ibelin family and so of Isabella and her mother, and provides the following insight. Having admitted that Isabella “did not want to [divorce Humphrey], because she loved [him],” the Lyon Continuation explains that her mother Maria persuasively argued that so long as she (Isabella) was Humphrey’s wife “she could have neither honor nor her father’s kingdom.” Moreover, Queen Maria reminded her daughter that “when she had married she was still under age and for that reason the validity of the marriage could be challenged.” At which point, the continuation of Tyre reports, “Isabella consented to her mother’s wishes.”

In short, Isabella had a change of heart during the church trial not because “woman’s opinion changes very easily,” but because she was a realist—who wanted a crown. Far from being a victim, manipulated by others, or a fickle, immoral girl, she was a intelligent princess with an understanding of politics.

|

| Isabella of Jerusalem, like her contemporary Eleanor of Aquitaine depcited here, was an intelligent and politically savvy woman. |

As for the church court, it was not “corrupted” by Conrad or anyone else. It simply faced the unalterable fact that Isabella had very publicly wed Humphrey before she reached the legal age of consent. In short, whether she had voiced consent or not, indeed whether she loved, adored and positively desired Humphrey or not, she was not legally capable of consenting.

No violent abduction, and no travesty of justice took place in Acre in 1190. Rather a mature young woman recognized what was in her best interests -- and the interests of her kingdom -- to divorce an unpopular and ineffective husband and marry a man respected by the peers oft he realm. To do so, she allowed the marriage she had contracted as an eleven-year-old to be recognized for what it was -- a mockery. Isabella's marriage in 1183 as a child prisoner of a notoriously brutal man not her marriage in 1190 as an 18 year old queen was the real "abduction" of Isabella.

Isabella, Humphrey, her mother Maria and her step-father are major characters in my three-part biography of Balian d'Ibelin.