In August 1186,

Baldwin V of Jerusalem died at the age of nine. His death had been anticipated

even before he became king, and it was the presumption that he would not live

to sire heirs of his body that led his predecessor and uncle, Baldwin IV, to

settle the succession in advance.

On his deathbed,

Baldwin IV had made his barons and bishops swear to seek the advice of the

Pope, the Holy Roman Emperor and the Kings of England and France about the

successor to his nephew, Baldwin V. The reason was simple: Baldwin V’s closest

relative (and so his heir presumptive) was his mother. While the constitution of Jerusalem allowed

women to reign in their own right, it did so only if they had a consort, a

husband capable of leading the feudal armies in the threatened Christian

kingdom. Sibylla of Jerusalem had a husband — but one that almost no one on the

High Court of Jerusalem considered worthy or capable of fulfilling that task.

He was the man who would ultimately lead the feudal armies to an unnecessary

defeat — but that is getting ahead of the story. At the time of his

brother-in-law’s death, Guy de Lusignan was simply a comparative newcomer to

the Holy Land, who had succeeded in alienating almost the entire local elite in

less than a decade.

Thus, when

Baldwin V died, the lords secular and sacred of the Kingdom of Jerusalem were

bound by oath to seek the advice of the most powerful men in the Latin West. The

kingdom was also surrounded by enemies that had been united by the ambitious,

charismatic and ruthless Kurdish leader Salah ad-Din, more commonly known in

the West as Saladin. By 1186, Saladin had declared jihad against the crusader

states and had already led four full-scale invasions in addition to numerous

smaller-scaled campaigns. There was a

short truce in effect and the forces of Jerusalem had so far succeeded in

beating off Saladin’s attacks, but the situation was clearly precarious. Under

the circumstances, the bishops and barons of Jerusalem were understandably

reluctant to await the decision of Western leaders notoriously at odds with one

another. The Kings of England and France (Henry II and Philip II respectively)

were engaged in nearly perpetual warfare against one another, after all. Another solution was needed.

The Constitution

of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was by this time a well-developed document, which

had evolved based on the unique history of the kingdom. The kingdom had been

established in 1099 as a result of the First Crusade. That campaign had been

led by a group of noblemen, who commanded jointly and did not recognize any of

their number as superior to the others.

When, having captured Jerusalem, they recognized the need for more

permanent leadership structures, they chose among themselves Godfrey de

Bouillon to “rule,” but he was still effectively little more than “first among

equals.” Furthermore, he explicitly refused the title of “king” on the grounds

that it would be inappropriate for a man to wear a crown of gold where Christ

had worn a crown of thorns. Furthermore, within a year Godfrey de Bouillon was

dead. The leaders of the First Crusade met again to “elect” their leaders, and

although this time their choice, Baldwin de Bouillon (younger brother of

Godfrey) had himself crowned, the precedent had been set that the kingship was

based less on hereditary right than on the consent of the leaders. By 1186 this

tradition had been institutionalized in the form of the High Court of

Jerusalem, which retained the right to “elect” the next king at the death of

the last.

|

| It is notable that the most famous militant orders established shortly after the Kingdom of Jerusalem likewise elected their leaders. Here the Hospitallers. |

Although over the

years the High Court had shown a strong bias toward choosing a close relative

of the previous king, on more than one occasion there were several viable candidates and the High Court had effectively exercised its rights. Furthermore,

the High Court had demonstrated the power to make contenders bow to its will as

when, for example, it forced the obvious heir to Baldwin III, his brother

Amalric, to set aside his wife of six years (Agnes de Courtenay) before he was

acknowledged, crowned and anointed.

Given the threat

Saladin posed, no one in the Kingdom of Jerusalem wanted to risk a long

interregnum after the death of Baldwin V, while the Pope, Holy Roman Emperor

and the Kings of England and France were consulted (and possible bickered) over

the next king. Furthermore, there were two obvious successors to Baldwin IV:

his elder, full-sister Sibylla — who was unfortunately married to the

unacceptable Guy de Lusignan, and his younger, half-sister Isabella, married to

a perfectly acceptable young man, Humphrey de Toron. Had Sibylla been married to a man more

agreeable to the High Court, there is little doubt that the High Court would rapidly

have recognized Sibylla. But Guy, as I said, had made himself so hated that

Sibylla knew she was facing serious opposition — as did Guy.

Rather than risk

a reversal in the High Court, the couple rushed to Jerusalem to seize the

throne illegally — i.e. without the consent of the High Court. Guy had secured

the support of the Templar Grand Master, who used his knights to secure control

of the Holy City. Once there, Guy and Sibylla, supported by Sibylla’s maternal

uncle the Count of Edessa, and her mother’s former lover the Patriarch,

badgered the aging Master of the Hospital into giving up the third key needed

to remove the coronation vestments from the treasury.

But there was

still the issue of popular opinion, and Sibylla felt compelled to promise she

would divorce Guy in order to garner sufficient support to carry out her

planned coup. Sibylla made her promise to set Guy aside conditional on being

allowed to choose his successor as her husband. On the basis of this promise,

Sibylla was crowned queen in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem in

August 1186. She then promptly broke her promise to her own supporters and

crowned Guy de Lusignan as her consort, saying she chose him as her “next”

husband.*

The problem was

that most members of the High Court were not in agreement and not in Jerusalem.

They were meeting in the royal city of Nablus to discuss the succession. While

surprised by Sibylla’s coronation, they did not accept it. In their view, without the consent

of the High Court, her coronation was invalid.

The High Court

(or the majority meeting in Nablus) decided that their best course of action,

therefore, was to crown Sibylla’s younger half-sister Isabella queen. They sought

to thereby create a legitimate ruler who could force Sibylla into irrelevance if not

submission. Given that the barons known to have collected at Nablus represented

the some of the richest of the baronies (Tripoli/Galilee, Sidon, Toron, Nablus,

Ramla/Mirabel and Ibelin), and probably included a number of unnamed barons as

well, any armed confrontation between the factions of the rival queens would

almost certainly have resulted in Sibylla’s forces being outnumbered. Sibylla is

known to have had only three supporters: Edessa (an empty title since 1144), Oultrejourdain — and the Templars.

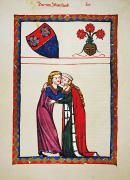

|

| An illustration allegedly depicting Isabella of Jerusalem and one of her four husbands. |

The High Court’s

choice of queen, Isabella, was the youngest child of King Amalric, and her

mother was the Byzantine Princess Maria Comnena. In 1186 she was 14 years old

and she had been married for three years to Humphrey de Toron. Although Toron was young, probably in his

late teens, his family had been in Outremer for generations. His grandfather

had been Constable of Jerusalem, and had been highly respected. Toron was

present in Nablus when the decision was made to crown his wife as an

alternative to Sibylla. That same night he fled Nablus, made his way to

Jerusalem and did homage to Sibylla.

When the bishops

and barons meeting at Nablus discovered what Toron had done, most resigned

themselves to the fate of taking oaths to Sibylla and Guy, but the two most

powerful barons did not. The Baron of Ramla and Mirabel refused to do homage to

Guy de Lusignan, preferring to abdicate his rights and titles to his infant

son. He left the latter and his lands in the care of his younger brother,

Balian d’Ibelin, and he left the kingdom altogether to seek service with the

Prince of Antioch. The other baron to refuse to recognized Sibylla and Guy’s

illegal coronation was Raymond III, Count of Tripoli. Raymond had been regent

of the kingdom for both Baldwin IV and Baldwin V. He ruled Tripoli in his own

right as an independent county, which did not owe homage to Jerusalem, and he

furthermore held the rich and vitally important barony of Galilee by right of

his wife. The latter straddled the River Jordan and surrounded the Sea of

Galilee. Raymond III refused to take the oath of homage, withdrew from court

altogether, and went so far as to seek a separate peace with Salah ad-Din to

protect himself from an anticipated attack on his territories by Guy de

Lusignan.

While the

departure of Ramla did not seriously weaken the kingdom because his brother was

a highly competent commander, Tripoli’s defection gutted it. The barony of

Galilee lay on the border and extended far toward the coast. It also owed one

of the largest contingents of knights to the crown. Without Galilee and

Tripoli, the Kingdom of Jerusalem became effectively indefensible.

Sibylla must have

known this, and all she had to do to save her kingdom was to keep her word,

i.e. to set Guy aside and marry a man acceptable to Tripoli and the other

disaffected bishops and barons. She refused. Her love of Guy was so great, she

preferred to see her kingdom torn apart, gutted and, ultimately, overrun by the

enemy.

To be sure,

thanks to the diplomatic skills of Ibelin, a temporary reconciliation was

patched up between Tripoli and Lusignan. Tripoli loyally brought his full

feudal contingent to the feudal call-up in July 1187. But Lusignan was still

king and he proved all his detractors right by leading the combined forces of

the kingdom to a completely unnecessary defeat at the Battle of Hattin.

Sibylla lost her

kingdom and three years later her life as well. She died of fever during a squalid siege of

the jewel of her former kingdom, Acre. Neither need have happened had she acted

legally and sought election by the High Court of Jerusalem, rather than seizing

the throne in a coup d’etat. Had she followed the constitution, it is almost

certain that the High Court would have recognized her as queen but required her

to set aside Guy before she was

crowned and anointed, just as her father had been forced to set aside her

mother. She would have been required to

choose a different husband, a man who enjoyed the confidence and support of the

barons of Jerusalem. Whoever that man might have been, he is unlikely to have

been as disastrous for the Kingdom of Jerusalem as Guy de Lusignan.

The exact timing

of the coronation of Guy is unclear. Some sources suggest she did it

immediately, during her own coronation; others that it was done later in a

separate ceremony.

The constitutional crisis of 1186 is described in Book II of my three part biography of Balian d'Ibelin:

A divided kingdom,

a united enemy,

and the struggle for

Jerusalem!

Or read more about the history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem at: Balian d'Ibelin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

So interesting, knew nothing about this period.

ReplyDelete