By early April 1232, it was evident that Lord of Beirut did not have sufficient force to relieve his castle at Beirut. After smuggling in some 100 fighting men to reinforce the garrison, thereby ensuring its ability to hold out longer, Beirut turned his attention to finding additional allies. The results were both significant and surprising.

The Lord of Beirut undertook a three-pronged effort to increase the forces at his disposal for the difficult task of relieving his beleaguered castle. First, he sought international support from the closest international neighbor, the Prince of Antioch. Secondly, he sought support from a maritime power, the Genoese. Last but not least, he sought support from the burgesses or middle class.

To secure support from the Prince of Antioch, the Lord of Beirut sent his son and heir, Sir Balian, to meet with the Prince in nearby Tripoli. Sir Balian took with him a marriage proposal sanctioned by (or originating from) King Henry of Cyprus, offering a marriage between King Henry's older sister Isabella and Prince Bohemond's younger son. Philip de Novare traveled with Sir Balian, as did Sir William Viscount, a wise and seasoned jurist. The party with Sir Balian took lodgings with the Templars and were, according to Novare, initially received by the Prince of Antioch with great honor and hospitality.

Abruptly, however, everything changed. First the Templars closed their doors on them, throwing them out. When they turned to the Hospitallers and Cistercians, who also maintained large houses in Tripoli, the other religious houses likewsie refused them shelter. At the same time, Balian was prevented from rejoining his father by the hostility of the barons controlling the road south. According to Novare, Sir Balian's life was repeatedly threatened by knights with close ties to the former baillies of Cyprus and allies of the Holy Roman Emperor

Sir Balian was forced to create lodgings for himself and his entourage in an unused grange, cleaning it out and furnishing it as best they could. He also sought to escape from Tripoli by requesting the Genoese to send ships. This route of escape was closed, however, when the rudders of the Genoese ships were removed on orders from the Prince of Antioch. Next, Sir Balian turned to the Sultan of Damascus, Malik al Aschraf, requesting a safe-conduct to pass through Saracen-controlled territory on his way to Acre. The Sultan obliged, but by that time the safe-conduct arrived it was no longer necessary; the direct route had mysteriously re-opened.

It is impossible with the information available to us to know exactly what was going on here. Novare attributes this sudden change in heart to "forged letters" from the Emperor, requesting Antioch not to render assistance to the Ibelins. Why such letters would have been forged is mysterious since the Emperor was engaged in a very open war against Beirut. For three years before this incident, he had repeatedly sent messengers to various lords of Outremer ordering them to arrest, disseize and otherwise harm the Ibelins.

Historians largely discount Novare's account of forgeries and his role in exposing them and are inclined to think Antioch simply changed his mind in the middle of the negotiations. Supposedly he (suddenly?) decided Beirut was going to lose his war and wanted to be on the winning side. Given the fact that Sir Balian arrived after his father had already abandoned his attempt to relieve Beirut, this hardly seems logical either. Nothing in Beirut's situation changed radically in the month Sir Balian was in Tripoli.

What might explain the sudden change in attitudes, particularly on the part of clerics, however, was the arrival of news about Sir Balian's excommunication. In March 1232, the pope excommunicated him for his marriage to Eschiva de Montbelliard, a marriage that was within the prohibited degrees. This would explain why all the religious houses refused him lodging and would have made him persona non grata at the court of the Prince as well. We will probably never know.

Meanwhile, in Acre, the Lord of Beirut with the aid of King Henry had been able to persuade the Genoese to throw in their lot with him. This was not so difficult a task, one presumes, for two reasons. On the one hand, the Genoese had a long history of hostility toward the Hohenstaufens. Under the motto, "our enemy's enemy is our friend" they were undoubtedly sympathetic to Beirut's cause. What turned sympathy into serious support, however, was the lure of the rich profits that could be made in Cyprus.

Up to this point, none of the Italian maritime powers had established a firm foothold on Cyprus. The Italian sea powers had won their privileges on the mainland by providing often vital maritime support to sieges during the early stages of the conquest of the coastal cities of the Levant. (See: https://defendingcrusaderkingdoms.blogspot.com/2018/06/the-italian-communes-in-crusader-states.html) Cyprus, on the other hand, had fallen into the lap of King Richard of England without any contribution by Italian navies. The Genoese were keen (to say the least) to get their foot in the door and secure the kind of trading privileges that promised to enrich their metropolitan city. They agreed to replace the Cypriot fleet that had been wrecked with a Genoese one.

Far more remarkable was Beirut's success in winning the support -- indeed, as events would prove, the tenacious and passionate support -- of a large portion of the middle class in the commercial heart of the kingdom, Acre. It was only three years since the people of Acre had expressed their opinion of Frederick Hohenstaufen by pelting him with offal and intestines on his departure. Undoubtedly, this act was not a collective act by responsible citizens, but it must have met with more approval than disapproval as one never hears of outrage much apologies or expressions of contrition on the part of the citizens of Acre to the Holy Roman Emperor. In short, Emperor Frederick was hugely unpopular in Acre because of the way he had behaved during his short sojourn in the Latin East. (For more see: https://defendingcrusaderkingdoms.blogspot.com/2018/10/the-curious-course-of-so-called-sixth.html)

Yet popular or not, what happened next had no precedent in the history of Jerusalem. It seems that after Riccardo Filangieri presented his credentials as the Emperor's deputy in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a delegation of nobles, headed by the former regent of the kingdom Balian de Sidon firmly objected to the siege of Beirut as it was an attempt to disseize a lord without due process and a judgment of the High Court. Filangieri replied that he was only following orders and that if anyone didn't like what he was doing they could take it up with Emperor Frederick II personally.

Aside from this being an abject admission of powerlessness, the answer made it clear to everyone -- from baron and bishop to the man on the street -- that Filangieri had no intention whatever of acting as an independent regent or, more important, of respecting the laws and constitution of the Kingdom. That made people nervous.

If Filangieri, in the Emperor's name, was prepared to attack a former regent, what might he do to ordinary knights and burgesses? If Filangieri was prepared to deny a man with close ties to royalty due process and the protection of the law, where was the Rule of Law for the man on the street? While it is claimed that the Lord of Beirut was popular, it was far more self-interest than personal affection that inspired men to take an unusual step: they decided to form a mutual protection society.

Historian Jonathan Riley-Smith puts it like this:

In Acre there happened to be a confraternity dedicated to St. Andrew and chartered perhaps by Baldwin IV and Henry of Champagne...[It] was unusual in that its membership was not limited to those of one nationality or sect but was open to all.... So barons, knights and burgesses assembed and sent for the confraternity's cousellors and charters. These were read out and the majority of those present solemnly swore themselves in as members.

Thereafter, they took to calling themselves simply the "Commune of Acre." This implied -- somewhat disingenuously -- that the men who had voluntarily joined represented the entire community of the city. That was hardly the case, but the Commune was sufficiently influential to meet with no opposition in Acre either. They next elected John d'Ibelin, Lord of Beirut, their "mayor," a position that was good only for one year requiring annual elections. As Riley-Smith makes clear, the Commune had no other functions than to resist the Emperor and his minions.

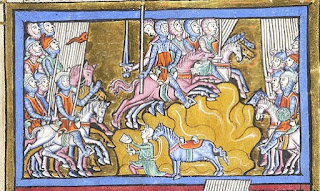

With the men of the Commune and the ships of the Genoese, Beirut was finally strong enough to make a new attempt at relieving his castle. Indeed, he felt that public sympathy had swung so much in his favor that he could risk an even more dramatic attack: an assault on Filangieri's power base in the city of Tyre.

The City of Tyre sat on an island, connected to the mainland only by a narrow causeway that was defended by three successive walls. The sea around the city was full of rocks and bad for navigation. Tyre alone -- of all the cities of the kingdom -- had successfully defied Saladin in 1187. It had remained a lonely bastion of Christendom for four years until the arrival of the Third Crusade. For Beirut to think that he might capture Tyre with his rag-tag army of Cypriot and Syrian knights, Genoese and burgesses sounds like hubris, not to say madness.

Yet despite the apparent futility of his task, Beirut had calculated correctly -- not because he could take Tyre, but because Filangieri could not risk losing it. No sooner did Filangieri learn of Beirut's objective than he abandoned the siege of the citadel of Beirut and sailed in haste to Tyre, leaving his army to follow by land. This prompt, apparently panicked, retreat suggests that Filangieri felt his hold on Tyre was not sufficiently secure. Perhaps he feared that some of the burgesses of Tyre would turn against him if they realized Beirut at the head of the "Commune of Acre" was approaching. Whatever his reasons, Filangieri withdrew to his base at Tyre, the siege of the citadel of Beirut was lifted. Sir Balian took possession of his father's city and castle. Beirut had established the "status quo ante bellum," but the war was far from over.

The story of Beirut's struggle with Frederick II continues next week. Meanwhile, these events are depicted in detail in my latest release:

Dr. Helena P. Schrader holds a PhD in History.

She is the Chief Editor of the Real Crusades History Blog.

She is an award-winning novelist and author of numerous books both fiction and non-fiction. Her three-part biography of Balian d'Ibelin won a total of 14 literary accolades. Her current series describes the civil war in Outremer between Emperor Frederick andthe barons led by John d'Ibelin the Lord of Beirut. Dr. Schrader is also working on a non-fiction book describing the crusader kingdoms. You can find out more at: http://crusaderkingdoms.com