|

| Seal of Philip II Capet |

Philip II Capet of France has gone down in French history as Philip Augustus, another way of saying Philip the Great or Philip the Magnificent. He earned this epithet primarily for wresting territory away from King John of England and restoring the control of the French monarchy over the vast lands in Continental Europe that had been controlled for half a century by John’s father (Henry II) and brother (Richard I). Philip II was able to reduce the English-controlled territories to a small enclave near Bordeaux. Having successfully subdued the most powerful of his insubordinate vassals, he proceeded to systematically re-establish the primacy of the monarchy over all the barons of France. By the end of his reign, he had greatly increased the wealth, prestige and power of the central government in Paris, built the Louvre, and established the University of Paris. He ruled a total of 43 years, from 1180 to 1223, and was the first king to style himself “King of France” instead of “King of the Franks.”

But most of this occurred well after Philip’s brief sojourn in the Holy Land, and the focus of this post is on Philip Capet at the time of and during the Third Crusade.

Philip had been born in August 1165, or eight years after Richard of England. He had been crowned king in late 1179 while his father yet lived, and became sole king of France at the age of 15 the following year. Almost at once he started fighting with the Count of Flanders over territory, and while this was resolved by treaty in 1185, Philip had meanwhile started making demands on Henry II for the return of his sister’s dowry. (His sister Marguerite was the widow of Henry the Young King, Henry II’s eldest son, who had died in 1183) This war with the Plantagenets was to last the next thirty years, with periodic truces.

The war between the Capets and Plantagenets was an intimate affair. Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II’s queen and mother of Henry the Young King, Richard, Geoffrey and John, had been married to Philip’s father. Philip had two half-sisters, who were Eleanor’s daughters by his father ― and they, of course, were half-sisters of the young Plantagenets also, by their mother. Philip’s sister Marguerite was married to Henry the Young King, making them brothers-in-law. Philip’s other sister Alys was betrothed to Richard. Henry the Young King and his brothers represented their father at Philip’s coronation in 1179, they attended the French court at other times as well. Philip knew the Plantagenets well, and they him.

In 1186, Philip succeeded in pulling the third Plantagenet son, Geoffrey, into his net. Geoffrey was preparing to rebel against his father (again), when he was killed in a tournament. Philip allegedly tried to throw himself into the grave from grief. Two years later, Philip lured the eldest of Henry’s surviving sons, Richard, into his camp by claiming (almost certainly untruthfully) that Henry did not intend to name Richard his heir. Richard publicly paid homage to Philip as his liege after confronting his father about his inheritance, and then fought at Philip’s side until his father was defeated, humiliated and dead. During this period of alliance, Philip and Richard were said to be so close that they shared a bed, a fact that has given rise to many accusations of homosexuality against Richard but, curiously, not against Philip.

In any case, everything changed the minute Richard was King of England. Richard and Philip might have been allies against Henry II, but they were enemies the moment Richard took up his father’s mantle. Richard Plantagenet had no more intention of playing humble vassal to Philip then his father had; he intended to retain control over all his territories. Philip and Richard were thus on a collision course from July 6, 1189 onward.

But on the surface, they had a common cause. They had both taken the cross and vowed to recover Jerusalem for Christendom. Richard had been the first prominent nobleman in the West to do so, and his subsequent actions attest to his sincere commitment to restoring Christian rule to the Holy City. Philip, on the other hand, is widely believed to have been pressured into crusading by his nobles and clergy; his subsequent actions seem to bear this out. Nevertheless, from 1189 to 1190 Philip was engaged in preparing for what would become known as the Third Crusade.

On July 1, 1190, Philip met up with Richard at Vezelay in Burgundy and traveled together at the head of their respective hosts as far as Lyon, before proceeding by different routes to the next rendezvous: Messina on Sicily. Philip was by now mourning the loss of his wife Isabelle, who had died giving him twin sons, who died shortly afterward. He, therefore, arrived in Sicily a widower. Evidently to the disappointment of the spectators ― but very indicative of Philip’s nature ― he made no great show of his arrival. He arrived in a single ship (i.e. ahead of his fleet) and immediately disappeared inside the castle on the harbor.

In Sicily, King William II, a staunch supporter of the crusader cause and brother-in-law to Richard of England, had died unexpectedly in November 1189, shortly before the Kings of France and England arrived. Lacking any direct heirs, the Sicilian throne had been seized by his illegitimate first cousin Tancred, who made the tactical error of placing the Dowager Queen of Sicily (Richard the Lionheart’s sister Joanna Plantagenet) under arrest.

Richard of England, in contrast to Philip, arrived in Sicily with his entire fleet and a with a showy fanfare of trumpets, fluttering banners, banging shields and the like. On landing and learning that his sister had been impressed, he demanded not only her release but the restoration of her dower portion (or compensation) and the full payment of everything William II had pledged to the crusade itself. Tancred capitulated rapidly, and Joanna Plantagenet made an immediate conquest: in Philip of France.

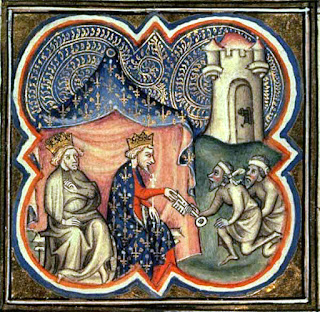

|

| This illustration allegedly shows Richard, Joanna and Philip in Sicily |

Accounts suggest that Joanna, who like Philip was just 25 years old, was beautiful (she was Eleanor of Aquitaine’s daughter, after all), and, of course, she was a dowager queen by marriage and a princess by birth. As Richard was already betrothed to his sister Alys, Philip may have seriously considered strengthening the bonds by taking Joanna to wife. Richard absolutely refused to think about this because he had no intention of marrying Philip’s sister Alys Capet.

Meanwhile, however, relations between Richard and Philip, already brittle with unspoken rivalry and latent hostility, had broken into the open when fights broke out between the local inhabitants and Richard’s troops. The English claimed they were being cheated, the locals claimed the English were disorderly and disrespectful. There were too many fighting men in a strange town, harassing the girls and probably being pick-pocketed, etc. The situation is perennial and resurfaces whenever there are large armies in foreign territory. Something ignited an all-out fight, and while Richard first tried to calm tempers, he soon lost his own and came to the aid of his men. Philip of France, probably out of spite for Richard rather than sympathy for the Sicilians, took the side of the locals against his fellow crusader. The break was so public and bitter that it took the efforts of many noblemen on both sides to get the two kings to reconcile.

The atmosphere between them deteriorated further when suddenly Eleanor of Aquitaine arrived in the company of Berengaria of Navarre. Richard now announced that he had chosen her as his wife instead of Alys. To an astonished and furious Philip, Richard explained that he could not possibly marry Alys because his father had known her carnally. The brilliance of this argument against a marriage that had been agreed years earlier was that this allegation stemmed from none other than Philip himself. Philip had used the accusation in his web of lies to induce Richard to turn against his father. As a result, Philip could do little more than swallow his own pride (and bile no doubt). But a marriage with Joanna was now obviously off the table. The kinship ties so elaborately devised by Philip and Richard’s fathers had all broken, and what remained was open and growing hatred.

But first there was a crusade to carry out, and the Kings of England and France publicly vowed to share all spoils in the upcoming campaign in the Holy Land. Then at the first opportunity, Philip embarked his army and set sail for the Holy Land on March 30, 1191.

Philip’s entire fleet crossed the Mediterranean without notable incident. On May 20, the King of France arrived off the city of Tyre, the last Frankish stronghold in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Tyre was controlled by a distant relative of Philip’s, Conrad de Montferrat, one of the two contenders for the throne of Jerusalem. Philip immediately threw his support behind Montferrat, bolstering his claim to the crown against those of his rival, Guy de Lusignan. He and Conrad together proceeded to the Christian siege of Acre. Here Philip brought not only new troops but new vigor to the siege, and at once erected a number of powerful siege engines.

However, he soon became ill with what the contemporary chronicles call “Arnoldia,” a debilitating illness that caused the loss of hair and nails and could be fatal. Furthermore, with the arrival of King Richard, there were two commanders in the same camp and frictions between them sparked almost at once. Allegedly, Richard refused to let his troops support at least one attack ordered by Philip. But then Richard too fell ill with “Arnoldia.”

Various assaults and above all the action of the siege engines continued as both kings gradually regained their strength. Most significantly, the arrival of the French and English fleet had enabled the sea blockade of Acre to become completely effective and no supplies, munitions or reinforcements were slipping into the city. By early July the Saracen garrison of Acre had reached the breaking point. The commanders of the Saracen garrison, therefore, sought a truce in which to seek instructions from Saladin. They told the French and English kings that they would surrender if Saladin did not come to their aid within a set period of time, asking to be allowed to take their arms and their moveable valuables with them and enjoy a safe-conduct to wherever they wished to go. King Philip, supported by his nobles, agreed. King Richard insisted they should not be allowed their arms and valuables. Negotiations broke down.

|

| A medieval depiction of the Surrender of Acre -- notably to Philip. Richard is beside him. |

Ten days later, with still no relief from Saladin, the garrison again sought terms and this time agreed to much harsher conditions: the return of the Christian relic known as the “True Cross” that had been captured at the battle of Hattin, the release of an unspecified number of Christian prisoners taken at or after Hattin, and the payment of 200,000 Saracen gold pieces, all to be delivered one month after the signing of the agreement. Members of the garrison (the numbers vary according to source) were to be held as hostages to ensure the release of the Christians, the remaining members of the garrison were free to go ― but without their arms or valuables. The kings of France and England accepted these terms.

On July 12, the hostages were surrendered, the remaining garrison marched out ― proudly by all accounts ― and the crusaders took possession of Acre after four years of Saracen occupation. They found the churches desecrated, but otherwise most of the city intact. It was divided equally between the French and English, with Richard’s men notably (and foolishly as it turned out) throwing down the banner of the Duke of Austria because that represented a claim to the spoils and Richard wasn’t sharing with anyone but Philip of France.

But now that Acre was in the hands of the crusaders, the issue of who was the rightful King of Jerusalem came again to the fore. As noted above, Philip backed the claims of Conrad de Montferrat (a kinsman), who was married to the sole remaining legitimate heir, Isabella of Jerusalem, and was supported by the High Court of Jerusalem. Richard, however, stubbornly backed the architect of the disaster at Hattin, King Guy, who was a vassal of the Plantagenet. After much bitter fighting, a compromise was found. Guy was recognized as king for his lifetime, but Conrad was recognized as Count of Tyre (to include Sidon and Beirut, if/when these cities were ever recovered) and heir to the throne at Guy’s death. Curiously, however, Guy’s elder brother Geoffrey, who had come out from the West with the crusaders, was also awarded the title of Count of Jaffa and Ascalon, the county that traditionally belonged to the heir of the throne. To be sure Jaffa and Ascalon were at this point in still in Saracen hands, but it was an ominous hint that the Lusignans did not really accept ― and did not intend to respect ― the agreement to make Montferrat king at Guy’s death.

With that dispute at least temporarily out of the way, Philip dropped a bombshell: he announced that he was turning over his share of all the booty to Conrad de Montferrat and intended to return to France. No one, not even his own nobles, had expected or approved of this abandonment of the crusade. His official excuse was “ill-health.” (He had either never fully recovered from the Arnoldia or he had contracted dysentery subsequently.) No one accepted this as a legitimate reason to break-off a crusade. Crusaders were supposed to achieve their objective, or die in the attempt. No one, however, was able to reason with or shame Philip into changing his mind. Despite alleged curses and bitter recriminations, Philip prepared to depart. Richard, suspicious that Philip’s intentions were to attack his lands in his absence, demanded that Philip swear on holy relics that he would leave the Plantagenet territories in peace until Richard’s return.

On August 1, 1191, Philip boarded a galley loaned to him by Richard of England and sailed for Tyre. He took Conrad de Montferrat and the most valuable of the Saracen hostages from the surrender of Acre with him. The exact date of his departure from Tyre is not recorded, but he was no longer in Outremer when the deadline for the delivery of the True Cross, captives and cash payment expired in mid-August. The decision to massacre the hostages fell to Richard of England alone.

Philip was back in Paris by late 1191. He immediately began undermining Richard’s authority and drawing the last and youngest of the Plantagenet brothers, John, into his net. His vow not to attack Richard during his absence was as meaningless as the crusader vow he’d taken before leaving for the Holy Land ― and as meaningless as the marriage vows he exchanged with Ingeborg of Denmark. Philip Capet, great as his legacy was for France, lacked any sense of personal honor, integrity, and a fear of God. While his qualities served his kingdom well, he remains for me a distasteful character.